Central Java Diaries

It is a seamless travel all the way up to Magelang, Yogyakarta, and the nearby towns and villages that form the face of centuries-old legacies of kingdoms. Starting well before dawn from Jakarta, we reach Borobudur early afternoon after making a couple of stops at rest areas on the highway. The peak of summer produces pretty good conditions for sightseeing during the journey itself. The mellow hour of the sunrise greets us as we climb Tol Layang MBZ (Mohammed Bin Zayed), Indonesia’s longest flyover highway and that runs for a little over 36 kilometres. As we close in on Cirebon, the early morning sunshine reveals hanging mist over paddy fields and trees. This slowly blooms into bright greenery as we touch upon the central Java land, with the sun gaining strength. As Indonesia’s weather is always unpredictable, be it west or east, the looming clouds over the Borobudur temple in the afternoon may not have been very promising for the next few days. But that’s the general rhythm every day in Indonesian summer.

Borobudur would be a sleepy town without its biggest pride – the largest Buddhist temple in the world whose name has become eponymous with the place. Even with its existence and charm, the place doesn’t look very touristy or very crowded as you would feel in downtown Yogyakarta. There might have been more shops and street vendors now, compared to my first visit some 20 years ago. However, the rules for visitors have changed a lot, whether you like it or not. Back in the days, you could walk straight to the ticket counter, enter the temple gardens and climb the balustrades all the way up to the monumental stupa and spend as much time there as you like. Deteriorating rock structures, formations and wayward habits of tourists have forced the authorities to take steps that should maintain the UNESCO Heritage for a long time to come. Climbing the temple structure now requires online booking and there is a cap of 1200 people per day. Sounds good for a serious attempt at preserving the temple, but there should be guards to warn and dissuade people from sitting on stupas and touching the Buddha statues. Rock erosion has been one of the most threatening factors jeopardising the temple structure, especially after the ash shower it was subjected to during the 2010 Merapi volcano eruption.

The street right in front of the temple’s eastern gate turns into an illuminated food rendezvous after dark. Modified cars and vans with colourful lamps decorating their chassis take curious children on a ride around the town. There are VW open vehicles that ostentatiously take tourists here and there. Their colourful bodies do not fail to attract anyone who visits the town first time. And there are the food carts that sell anything Indonesian, Thai, Korean and western delicacies. Visitors from bigger cities may see this as the locals’ desire to create a global environment for themselves in a small historical town. Under the hanging lamps in their carts, the vendors prepare various foods – Mie Bakso, Nasi Goreng, Sosis Bakar, Takoyaki, Kimchi, Burger and what not. Right in front of the gate of the temple that closes after 5 pm is a local artist who arranges tiny canvases for children to paint their favourite toon characters. Not far away from this, smoke rises from a sate vendor’s charcoal signalling the start of the evening food hunt.

The Buddhist temples of Pawon and Mendut were constructed at the same time with the Borobudur temple. The three temples are positioned in such a way as to fall within the same line of axis from west to east. Both Pawon and Mendut are said to be part of the Borobudur temple as the trio complete the cosmology according to Buddhist beliefs. The temples narrate the Buddha’s life story from desire to nirvana just as it is depicted in the three layers of the Borobudur temple itself – Kamadhatu (the base structure symbolising one’s desires), Rupadhatu (the five layers in square shapes symbolising the removal of desire, but retaining the form) and Arupadhatu (the three layers in circles and the biggest stupa symbolising nirvana). So, on historical and religious points of view, the visit to the Borobudur temple only reaches completion after visits to the Pawon temple and the Mendut monastery. However, you have hardly any visitors to the latter two which lack the majestic and imposing outlook of the biggest one and have easily merged with the residential neighbourhoods.

Green Villages

Not every village in Indonesia throws plastic into ditches and rivers allowing coca-cola bottles and straws and cotton buds to end up in the ocean. A fully guided visit to these green environments will reveal how much people care to preserve the cleanliness of their surroundings and how they are united in their endeavour to sustain a pollution-free world. The words and actions illustrated by our guides, local people and people working on small scale food industries are evidence enough to sense the teamwork and common understanding that villagers have on environment protection. A Dokar (small horse cart) trip brings us to a small house in the village of Candirejo where an elderly couple are engaged in making Tempe, fermented soybean, Indonesia’s favourite side dish that goes along with rice. The man steams the raw beans in two large containers while the woman is busy cutting banana leaves to wrap the finished Tempe. The beans are being steamed using wood fire. Once out of the containers, the beans are placed on a circular thatch tray and are dried using a hand-held fan. In the entire process no electricity or electronic equipment is used, making it a very sustainable enterprise.

Turning to another alleyway, we enter the visitors’ area of a lady’s house where she is busy sitting among shopping bags, purses, totes and other articles, all made out of recycled plastic. She is currently in the process of designing a new multi-purpose bag when we reach there. A bag of that kind with a moderate size could be finished in an hour. She produces around 25-30 bags a day depending on demand and the materials that are available.

The village has several rest houses or guest houses where travellers can get in and spend time chatting and having snacks and drinks. These places have names such as the one we get in – Omah Kopi – making them sound like usual warung or small restaurants but are reserved for only travellers coming from outside of the village. They do not function like restaurants basically. We are greeted by an old lady who lives there and brings us traditional snacks like fired cassava, Wingko (a traditional Indonesian pancake-like snack made from coconuts) and banana fritters along with tea. No tissues are provided as the village keeps to its stance of going eco100%.

The next day, we set off for a unique village that lies on the lap of a volcano which last erupted sometime in the 18th century. Mt. Sumbing (which you can see on a diagonal line with the Borobudur temple early morning on clear sky days) is home to the village of Dusun Butuh, popularly called Nepal van Java. As we are not lucky enough to see the colourful houses of the village in a flow-down pose down the mountain owing to thick fog, we decide to take motorcycles to go up. Life here is like hanging on to some tree branches, but for the natives of Dusun Butuh, especially for the ones who take us on their bikes, it is their best comfort zone. Around the village are vegetable gardens spread all over the mountain’s foot. Like in Candirejo, the villagers are particular about not throwing plastic recklessly. On our way up, one of the bike riders stop quickly to remind an outsider not to put Styrofoam box on the roadside. He gets off the bike and guides the man to a bin where the latter could deposit the trash appropriately.

The relentless fog means we cannot not see the village nor the vegetable cultivation in their resplendent best, however, we opt for a walk along the veggie plantations in Sukomakmur (on the west side of the village) and chat with ladies working on scallion fields. We can only see their outlines as we get within 10 metres from them.

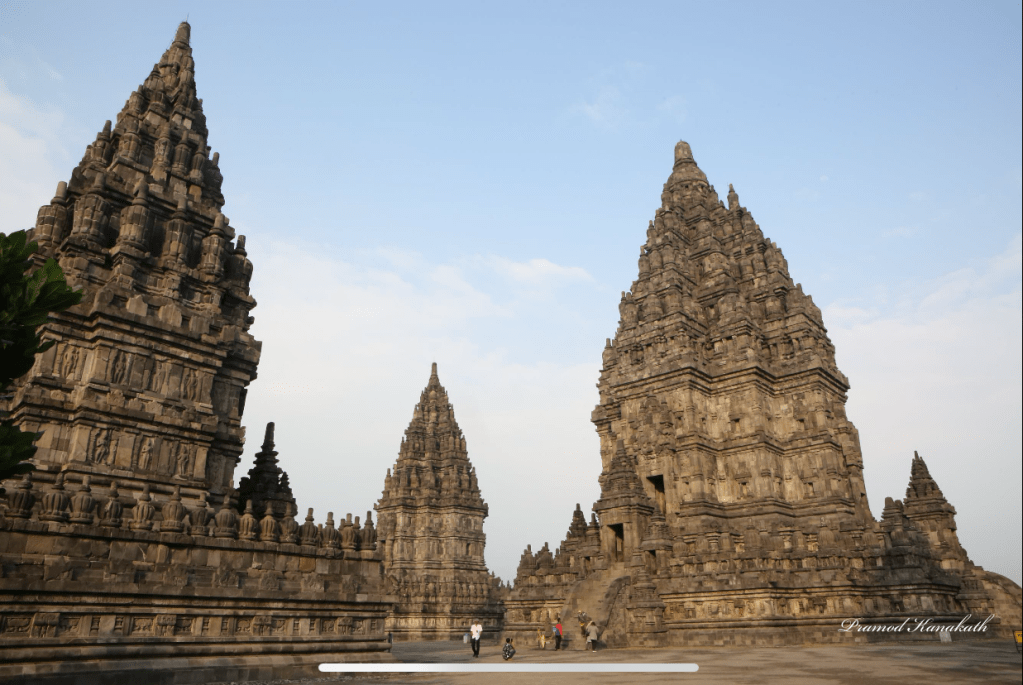

Remnants of Sanjaya Dynasty

When visiting Java’s ancient Hindu-Buddhist temples, the first thing that I am reminded of are the legends and myths that surround each of them. They make the temple even more mysterious, propelling me to forget the efforts of the craftsmen and the architects who hoisted them. Temple-hopping through Prambanan, Sewu, Plaosan and the remnants of the palace of Ratu Boko, my mind is pre-occupied with the thoughts of Roro Jonggrang and Pramodawardhani. While Roro Jonggrang’s story is all too famous and depicted and used as theme by performers, organisations, resorts and restaurants, Pramodawardhani is less heard of. Pramodawardhani is the daughter of King Samaratungga of the Shailendra dynasty in whose time the Borobudur temple was constructed. King Samaratungga is said to have died before the completion of the temple and it was the Princess, his daughter who oversaw the finishing after getting married to the Hindu king Raka Pikatan from the Sanjaya dynasty. I have a very close look at the face of the statue of goddess Durga in the Prambanan temple after learning that Pikatan may have used Pramodawardhani’s face as model for the Durga statue.

The inter-religious marriage and the presence of Sewu temple within the complex of the Prambanan temple are some of the striking examples of the harmony that existed between the two religions during that period.

A few kilometres from Prambanan lies Candi Plaosan, the Buddhist temple whose reconstruction takes place at a snail’s pace. This is probably the most challenging for the authorities as the two parts of the temple are divided by a road. Land acquisition with owners’ permission and relocation of local inhabitants will need to be sorted out in order to carry out the task in a smooth manner. Out of the 283 temples, only 20-30 have been restored so far. Nevertheless, there is a charm on the ruins. Even parts of reliefs and the scattered stones whisper stories.

The Keraton, the Batik and Malioboro

Back in 2006, I reached Malioboro on a becak from the nearby railway station with a friend and found a prominent-looking hotel called Hotel Cahaya Kasih. The street was the main thoroughfare of Yogyakarta town as it is now. There were the Andong (the biggest horse cart) and the Bendi (smaller than Andong, bigger than Dokar), shops that sold clothes, souvenirs and snacks, plus one mall, The Malioboro Mall. I am amazed to find Cahaya Kasih still standing proud though visibly dwarfed and sidelined by new, bigger players. The mall has received a timely facelift and is competing with at least two new players in close proximities. The street all along is a morph of the past. The footpaths on the left and the right are concretised with royal style lamp-posts and chairs for people to sit. They are wider than the road itself which is still dominated by the Andong and the Bendi, and motorised becak, run by youngsters. The old generation seem to stick to the pedalling ones, at least some of them.

The markets in Malioboro come alive in the evening hours. Anyone who gets into these markets is someone who not just realises the inconvenience of being inside them, but also who loves being there, surrounded by strangers, clothes, food, souvenirs and performers. The roads get clogged too, with cars and other vehicles forced to do parallel parking due to want of space in a fast-progressing, sophisticated Yogyakarta.

Amidst these captivating chaos of street food and markets, we get into a batik showroom called Hamza Batik, run by a prominent Indonesian actor who dons female roles. The scene inside is no different here as people jostle between rows of fine-woven batik clothes, but the vibe is more of an educated crowd. Also, there are entertainments on offer. A large diorama of a Javanese royal household with a life-size statue of a lady sitting on a chair and a circular space on the floor for people to sit and take photos is being explored by customers. Next to it is a lady offering a pot of Jamu to visitors for a moderate price. She has 4 different bottles of potions that can be mixed in order to create the final drink. Weaving batik and making jamu were some of the most popular recreational activities women were engaged in during the dynastic eras in Java. The tradition still continues in its villages.

Except for a high-tech looking museum with laser shows, the Keraton, the Sultan’s palace, is probably the only thing that may not have changed in the city through the years. The palace guides are still middle-aged women adorned in their light green top and batik skirt, sitting on a patio reserved for them while waiting for visitors who ask for their services. The open halls exhibiting the Gamelan collection, the gongs and other musical instruments lie exactly as they must be etched in everyone’s memory from the first time. These days, the Taman Sari, the adjacent water castle of the royal family gets more visitors than in the past as the architectural style evokes more taste buds.